A hard conversation about police violence and gun control

A robust Second Amendment right comes with deadly serious responsibilities

Last month, a 22-year-old Black man in my hometown was fatally shot by a police officer during a traffic stop, not far from where I spent my own adolescence. I didn’t know the young man or his family, but my social feeds suggest he’s not very far removed from people I grew up with. My sympathies to them and everyone else who is affected by this tragedy. Out of respect for his family and loved ones, I don’t use his name because, ultimately, what follows is not about him, but rather how we should think about what happens in our streets and neighborhoods.

The initial anti-police rhetoric after his death was predictable, given the nationwide aftermath of George Floyd’s death generally and the Fort Wayne Police Department’s violent overreaction to the 2020 protests specifically. Activists called the incident an “execution,” as a bystander video had gone viral before the body camera footage was released. Like vengeance, blame is a natural response to traumatic violence, but time and information can provide a different perspective.

The law regarding police shootings (briefly)

Because the investigation is ongoing, I recognize that currently unknown facts may come to light that change my mind, but given the law and the currently available evidence, the officer’s actions will likely be deemed justified.

As Radley Balko and others have noted before, legally justified doesn’t mean necessary or morally just. That said, having cataloged thousands of abuses of police authority and closely followed dozens of government responses to “bad shoots” as part of my job, nothing about this incident as yet resembles a cover-up or other misconduct.

Without getting into the exact details of the law, the basic standard for justification of lethal force is that the officer must be reasonably fearful for his life or for the lives of others. This does not mean that the officer must determine for an absolute fact that his would-be assailant is armed with a lethal weapon. As one example, if a person draws a metal object out of their pocket in a standoff, holds it like a gun, and points it at someone, an officer may be justified in shooting the person even if the object turns out to be a bathroom fixture. Whether the standard ought to be raised is a separate question, but this is the state of the law now.

In the present circumstance, the young man repeatedly disobeyed clear officer orders to keep his hands visible—and despite protests from the driver of the car to do so—and kept reaching for a bag that apparently contained an AK pistol. There are few things worth noting about these facts.

Possessing a gun is not proof of past or future violence

First, possession of a gun—even illegally—does not necessarily indicate malicious intent. We’ll likely never know what the young man was trying to do in those crucial moments. Indeed, the gun may not have been his, but happened to be near his seat and he was trying to hide it out of panic. When I was around his age, it would not be unlike me to be high in a car at that time of evening—though never to my knowledge was I in a car with a gun—and the prospect of being arrested and charged would have been terrifying, whether I was high or sober. (I am not suggesting the young man was intoxicated; I mention it only as one possible, familiar-to-me, and non-threatening explanation for non-compliance with the officer’s commands.)

Nevertheless, disobeying the officer was a fatal mistake. It does not mean he “deserved” to die, but the harsh reality is that the young man’s actions led to his death.

Neglecting the duties of gun ownership

Assigning responsibility for his own death may seem unfair, particularly to those who believe that police are too quick to use force. One activist posted to social media that:

“To those who say the video…mentioned that he had a gun–if he had a gun that doesn’t mean he deserved to die. Everyone has the right to own a gun in the US. That right isn’t revoked because of skin color.”

I have written previously about the very real double standards Black gun owners face when exercising their Second Amendment rights. And I’ve often thought about writing about how many gun regulations disproportionately inhibit responsible Black gun ownership. Given the young man’s local reputation and permissive gun laws in the state, it’s likely the gun was entirely legal. But this young man failed to protect and govern himself responsibly in proximity to that firearm.

And to be perfectly clear: if a police officer knows or strongly believes you have a firearm, he has the authority to render himself safe from that firearm. As a gun owner, I must understand and respect that. There are techniques to reduce officer tension and apprehension. But, say, if I shoot someone in self-defense with my registered and legally carried pistol, even as a white-looking man in my late 40s, I expect to be treated like a criminal suspect when officers respond to the call I have the duty to make to report the shooting. I will be disarmed—likely at gunpoint—and very likely handcuffed and left on the ground, following what was likely to have been a traumatic event for me. If, instead, I do not follow instructions and reach for my gun at that moment, I would expect to be killed by the responding officers. These are the ancillary costs and duties that come with the rights to bear arms and personal self-defense.

I have also written repeatedly being a young Black man will make an antagonistic police posture more likely. Of course that’s not fair, but this unfairness is why “The Talk” Black parents give their children is fundamentally about survival. One only need look to the killing of Philando Castile to recognize the dire consequences of a police officer overreacting to a Black man with a legal handgun. I do not dispute that grim reality. But not every tragedy is a policy or procedural failure to lay at the feet of the police.

Multiple layers of irresponsibility

But we also need to talk about the firearm. According to reports, the gun recovered is a Draco AK pistol that uses 7.62 x 39 ammo. This is a photo of one of the smaller versions of the gun available online:

While technically a pistol, it is not a handgun in any practical sense. It uses higher velocity ammunition designed for carbines and most often used in AK-47 rifles, more appropriate for shooting at intermediate distances—50 to 100 yards—much further than what is reasonable for immediate self-defense. When you read about medical reports of mass shootings from AK and AR rifles and the profound damage they do to the human body, that damage comes from those large, high velocity rounds.

For a comparison, here is a photo (from left to right) of a defensive 9mm round, a defensive .45 ACP round, and a similar (but smaller and faster 5.56 NATO) round to the type used in the weapon recovered at the scene. All these rounds are potentially lethal—and are meant to be—but the bigger and faster they are, the further they go and the more damage they can do.

The 9mm round is the most common round for handguns and good for personal defense in a carry pistol, which is typically smaller than other pistols. The .45 round has more “stopping power” but is somewhat less common for carrying because the trade-off for power is fewer rounds in a magazine, though some gun owners make that choice. The third is, well, something I’d only use in defense amidst violent anarchy or urban combat. (Watching the police rush past my home en route to the Capitol on January 6 made those scenarios far more likely than I ever thought realistic, but that’s a different issue for another time.)

While it is possible the gun owner thought it would be useful for responsible self-defense, that Draco is not a reasonable weapon for that purpose. In this post, I am not concerned with the constitutionality or wisdom of owning or banning AKs broadly; I am explaining that, as a pro-gun guy, I cannot justify carrying that weapon for self-defense in an urban setting, let alone transporting it uncased in the passenger compartment of a car. Legal or not, carrying that gun that way was a terrible decision, and lawmakers ought to consider removing it from carry-eligible weapons.

When I started writing this piece, I was not considering whether some of the local media would seize upon the kind of gun it is. The gun and its ammunition caliber jumped out to me when I read the initial stories because of their impracticality and implicit dangerousness (i.e., greater chance of bystanders being killed or injured) in an urban area. Subsequent stories describing the gun being a popular gun among gang members is an all-too-standard post-shooting public relations tactic police use that I want no part of. While what the police say about the gun’s popularity may be true—the Draco has apparently made it into rap lyrics—the unsubtle implication is that the young man “was no angel” and that’s simply not relevant here. Everything I write is just as true if he made innocent but fatal mistakes or if he were a hardened and violent criminal.

“Constitutional” does not mean responsible

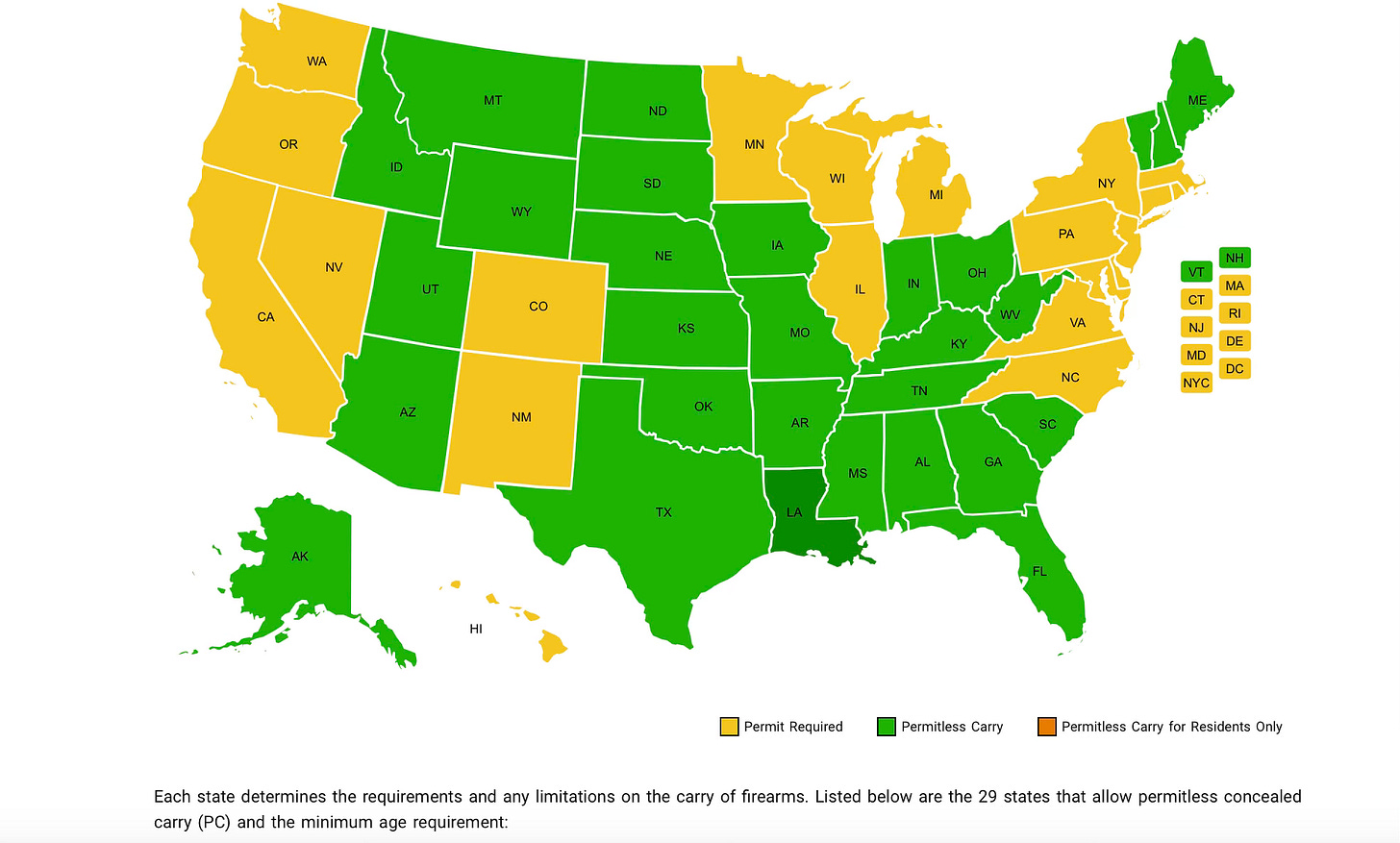

In 2022, Indiana became a permitless concealed carry state, politically known as “constitutional carry.” This means an individual is presumptively allowed to carry a concealed weapon without obtaining a permit unless they are statutorily barred from owning guns (e.g., convicted felons and domestic abusers cannot own firearms). From a criminal justice perspective, I think a pivot away from seeking and then harshly punishing people who carry firearms is generally a good idea. But as a public safety matter, not requiring a basic firearms safety class to carry loaded guns in public goes too far in the other direction.

screenshot from usconcealedcarry.com

Requiring basic lessons and informed recognition of the duties and responsibilities that come with the right to armed self-defense need not be a burden. Most shooting ranges I’ve visited require some sort of basic instruction on gun safety or a demonstration of proficiency in basic gun mechanics to rent a firearm. These are basic steps a person must take to shoot in a facility meant for gunfire. Yet there is no requirement that a gun purchaser shows any proficiency or knowledge of firearms to purchase a gun.

And in a growing number of states, there no such requirement for those who carry loaded guns among the general public. As someone who spent several years working to expand the individual right to bear arms, I think that is stupid.

I grew up with guns in the house; I learned basic gun safety from a very young age. My first gun was a .38 special revolver that my father used as his police sidearm. When I wanted to buy a semi-automatic handgun—that is, typical handguns cops and bad guys alike use TV and in movies—I went to a friend that had extensive firearms knowledge and we practiced together at the range. Previously, I’d taken two basic firearms classes that were offered to me free of charge that introduced me to several common handguns and rifles.

2007: The year I fell in love with the AR rifle. (N.B.: This rifle is very illegal where I live.)

Not everyone has these resources within their familial and professional networks. And people who don’t know where to find these resources may be more likely to buy weapons without that information and for reasons other than the most practical self-defense. Again, I don’t know the story about this gun and this young man, but these are the circumstances in which many inexperienced gun owners across the country now find themselves.

And I don’t think permitless carry laws will lead to massive murder increases or new crime sprees; most people who commit gun crimes do so with stolen and illegal guns and the vast majority of gun owners will never commit crimes with their firearms. Nor do I think basic firearm safety instruction will prevent all bad decisionmaking, impulsive violence, or negligent discharges that result in death or injury. But there are fundamental concepts and procedures that all gun owners ought to know, and the state is in a position to require that first-time gun owners learn them. The absence of basic firearms instruction will likely lead to needless accidents and tragedies entirely separate from police interactions.

Making policing less safe for cops and gun owners

Because the public expects police officers to intervene in volatile situations in a country with more firearms than people, cops perform patrol duties and respond to calls for service (i.e., 911) while armed. I have written often and at length about reducing the number of unnecessary and antagonistic police contacts with the public, particularly with young Black men, but it is not an argument against proactive policing altogether. Targeted patrols in uniform and marked vehicles can reduce violent crime without violating civil liberties of the people on their beat.

There is a dashcam video from the late 90s that some (many?) police departments use in training to demonstrate the potential dangers of traffic stops. In the video, a county deputy is conducting a stop in Georgia after he pulled over a pickup truck for driving 98 mph. The driver is acting erratically and the deputy draws his weapon. He repeatedly tells the driver to pull his hands from his pockets and step away from the truck he was driving. After the suspect mocks the deputy, he pulls an M-1 carbine out of the cab and shoots the deputy repeatedly, including a final mocking coup de grâce. The dying screams of the of the deputy are gut-wrenching and will stick with most viewers for a very long time. (The pickup truck driver was a mentally ill war veteran and was eventually executed for the killing. You can read a post-execution account of the case here.)

I have questioned the use of this video to train cops because it teaches them to be afraid of the people they stop. And recall the basic standard for an officer to shoot a person: fear is the baseline justification for police violence. New York attorney Scott Greenfield coined this as the “reasonably scared cop rule,” and it’s easy to see how the incentives skew against an agitated person stopped by a cop. Nevertheless, it is true that a weapon within the reach of someone not responding to police commands to keep hands visible is sometimes how cops die. Changing the law to reflect a higher standard for lethal force may be appropriate, but that is not the legal realm in which gun owners currently live and we must conduct ourselves accordingly.

It’s into this legal milieu that permitless carry laws come into being. Not teaching people how to carry and transport arms responsibly puts officers, gun owners, and civilians in unnecessarily fraught and dangerous situations. Certainly, cops should be trained not to freak out when they see or learn about the presence a gun. At the same time, gun owners who choose to carry their weapons should be taught how to do so responsibly for the safety of themselves and others.

All rights come with correlative duties and responsibilities. Permitless carry states ought to do more to make sure their citizens are aware of what those duties and responsibilities entail to minimize needless tragedies and suffering. Invoking the Constitution doesn’t magically transform weak laws into good policy.

Until next time, wishing you peace, love and soul…

JPB