Welcome to the latest edition of The Blanks Slate!

I’m back to about 95 percent health, with residual COVID symptoms not unlike my seasonal allergies, so I’m effectively back to normal. Thanks to all who have reached out and inquired after me.

What I’ve read:

I am not going to comment substantively on the presidential debate last Thursday. There’s been enough virtual ink spilled over it and venting my spleen about it isn’t going to add anything useful.

Nothing has changed insofar as Donald Trump should not be reelected to the presidency. He’s a threat to the Republic and it is a living nightmare that millions of Americans don’t recognize this basic fact. I will say, however, The Bulwark’s Jonathan V. Last gets it: “Debating is easy when you are allowed to lie with utter impunity.”

Because COVID basically forced a week off for me, I’ve been playing catch-up and not reading a lot online. However, I was persuaded to make time for this personal essay by Aylet Waldman in New York Magazine. She chronicles an intensely personal journey to Israel with her elder half-brother, Yosi, as she pieced together the truth about their idealist Zionist father and the concept of liberal Zionism generally.

A snippet:

On our drive south to Kissufim, Yosi announced firmly that he was neither a subject of nor a partner in my investigations. “I’m just the driver,” he said. And for the next two hours, he talked without pause. When our father told his parents that he would avoid combat in 1948, it was either a wish or a lie, Yosi told me. In fact, he was a machine gunner who would have fought in intense battles in which those Arabs he claimed ran at the sound of a loud noise tore his unit to shreds, likely killing many of the young people he had recruited and trained. “It’s about six months that there is continuous fighting and they continuously lose people,” Yosi said. “You go out at night and you don’t know if you’ll come back in the morning.” For some, those battles continued after the war, into the early 1950s. “They did crazy things. All kinds of stupid raids.” Raids on whom, I asked. “Gaza,” Yosi said.

I sat stunned. Raiding Arab villages long after the end of the war was not part of the picture of Zionist idealism my father had painted for me. During raids, Yosi said, young kibbutzniks would steal donkeys or other things in retaliation for similar thefts by the Arab villagers across the border in Gaza. These incursions and counter-incursions were not limited to thefts.

It is a challenging piece because it is a reckoning of family and national histories and, specifically, the lies people tell themselves and each other.

Over at the London Review of Books, Eric Foner—eminent historian of the American Civil War and Reconstruction eras—reviews a recent work that deals with our collective self-deception: Richard Slotkin’s A Great Disorder: National Myth and the Battle for America.

An excerpt:

Where do national myths originate? They do not emerge by happenstance. Rather their creation and spread are an exercise of power. Influential historical actors, from antebellum slaveholders to the moguls of Hollywood and those Slotkin calls the ‘political classes’, have attempted to develop and disseminate broadly acceptable myths to serve their own interests. Then there are historians, seemingly well positioned to invent and develop new national stories. Each side in the culture war, Slotkin writes, appeals to American history. But historians have not taken on the task of devising a coherent national mythology that can bring unity to a fractured republic. Instead, Slotkin notes with dismay, students in red and blue states are being taught radically different versions of the nation’s past. All this, he writes, reflects not simply divergent opinions on specific issues, but ‘disagreements about the fundamental character’ of American institutions and ‘the purposes of the American nation-state’.

A nation of immigrants succumbing to blood-and-soil nationalism is a particularly galling vision of the future, and suggesting that our best defense is a new noble lie is not a comforting solution.

Something to think about:

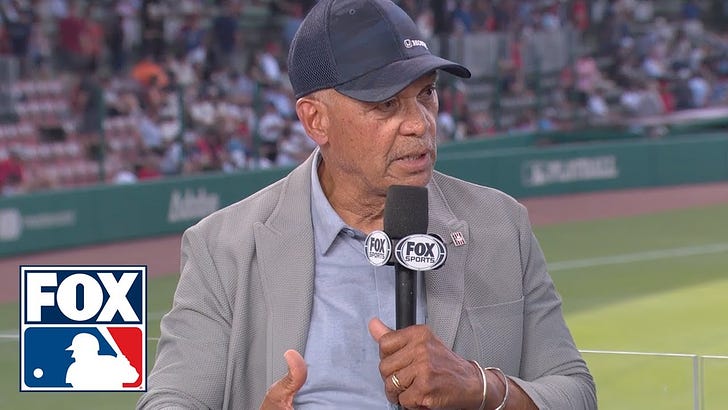

And finally, just after the passing of baseball legend Willie Mays—who I believe was the greatest baseball player of all time—Major League Baseball played a game at the oldest professional ballpark in the country, Rickwood Field in Birmingham, Alabama, to honor the Negro Leagues and their players. Although the full video includes some happier baseball-centric conversation that I would recommend to fans, I wanted to highlight this segment for everyone because of what Reggie Jackson went through as a player.

Reggie was on the Yankees when I was born, and he was still a celebrity when I was growing up. The myths that gloss over the shameful norms and outright horrors of our national history have not been long enough in the past to outlive the people who experienced them, and that we still have to fight to tell the truth is exhausting.

Until next time, wishing you peace, love, and soul…

JPB